How officials and popular academics have responded to disaster victims in the wake of Tokyo Electric Power Company's Fukushima nuclear accident

Toshinori Shishido (English translation by Sloths Against Nuclear State)

February 4, 2016

About the author

I worked as a full-time teacher at a public high school in Fukushima for about twenty-five-and-a-half years, until July 31, 2011. During the first four years of my career, I taught at Futaba High School in Futaba-machi, home to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Naturally, I have heard stories about the harsh working conditions of nuclear workers. For example, in a certain area of the power plant, working for 10 minutes would exceed the legal maximum daily radiation exposure limit. So each shift was officially recorded as 10 minutes even though their actual worked shift was 8 hours. The workers would primarily wipe water leaking from the piping surrounding the nuclear reactor. When workers died of illnesses like cancer, their families received unusually high amounts of cash as lump-sum payments, while actual workmen’s compensation insurance was not provided.

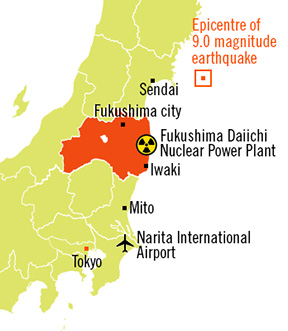

At the time of the 2011 nuclear accident, I was living in a city 53 kilometers (33 miles) away from the power plant with my wife and two children. I was working at a public school 60 kilometers (37 miles) from the plant.

After the accident, on the evening of March 15, 2011, the maximum airborne radioactive levels of 23 microsievert/hour was detected in Fukushima City, where I worked. Outside the school the following day, however, the annual school acceptance announcements were held as scheduled. Several faculty, including myself, met with the principal to insist that usual outdoor announcement be cancelled as to avoid having young students exposed to radiation–but the announcement event was forced outdoors. The principal cited reasons such as, “the Fukushima Prefecture office strongly supports the outdoor plan” and he “had no choice as the school principal.”

From April 2011 on, aside from the prohibition of outdoor gym classes, neither my school nor the Fukushima Board of Education took any measures to prevent further radiation exposure for students. The school had students practice club activities outdoors as usual. Indoor club athletes were made to run outdoors as well, without any protective measure against radiation exposure. Despite the standard practice, measures such as gargling, washing hands, changing clothes, and showering weren’t deemed necessary for students when returning from outdoor activities. Since I had some knowledge about radiation exposure, I advised the students to take caution to remove potential contamination whenever possible. However, in response to my giving the students advice to prevent radioactive materials from entering the building, I had been cautioned by the Fukushima Prefectural Board of Education, in the form of official “guidance” which forbids me to even talk about radiation and nuclear power plants to the students. Given that I was officially barred from protecting students from radiation exposure, I decided to make my move: along with my family, I evacuated my hometown and relocated to Sapporo city in Hokkaido. Once we evacuated, we found out about a financial system by Fukushima Prefecture which supports voluntary evacuees from the areas outside of the officially restricted zone (though it only approved applications from evacuees pre-December 2012; those who evacuated thereafter would not be financially supported).

I have been teaching part-time in Hokkaido. Since finding out that within the public school system the Fukushima Prefecture Board of Education can intervene to oversee public high school relocation anywhere, I have been teaching at private schools only. Aside from my part-time job, I have been involved in a nuclear power plant damages lawsuit as a plaintiff as well as a member of the refugee organization.

1. Fukushima Prefectural Government and the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO)’s Fukushima Nuclear Accident

The reactors at the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, especially Unit 1 and Unit 2, were delivered and installed from the US after the US manufacturer finished all of their construction. As for Units 3, 4, 5, and 6 the Japanese manufacturer added their own “improvements” to the original structure.

I will try to avoid a lengthy explanation. TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant frequently had accidents immediately after beginning operation and the nuclear workers’ exposure levels amounted to twice to ten times the average exposure dose at other nuclear plants. Furthermore, TEPCO kept a lot of serious accidents hidden from Fukushima Prefecture and the Japanese government. TEPCO proposed using Unit 3 for so-called pluthermal power generation, utilizing fuel which can contain weapons-grade plutonium in order to reduce the plutonium surplus in Japan. Eisaku Sato, then-governor of Fukushima, strongly objected to the proposal.The Japanese government arrested and convicted Governor Sato on bribery charges with the amount of the bribe recognized as “zero yen.” They drove him to resign, then elected Yuhei Sato as the new governor. As described above, neither the Fukushima governor nor the organization called the Fukushima Prefectural Government had power over TEPCO.

2. Nuclear accident and the Fukushima Prefectural Government

March 11, 2011, when a massive earthquake hit a wide area including Fukushima Prefecture, the building of the Fukushima prefectural office (which had been planned to function as a Disaster Response Headquarters) was damaged in the earthquake. The headquarters were set up in a small building next to the main office building to serve temporary functions. The prefectural government has never publicized records of proceedings and documents from over 20 meetings in the beginning. From the 25th meeting, they finally began keeping records of proceedings.

At the time, the temporary disaster response headquarters was believed to have had little to no communication lines, and had reportedly only two satellite mobile phones. Although the communication infrastructure began to be rebuilt gradually, what was happening then still remains largely unknown. There has been no official investigation into the correspondence between the local governments, the central government and TEPCO, and no evacuation orders to the local communities.

As far as public record goes, the only time Fukushima Governor issued an announcement in the first week was on the evening of March 14th. “Follow the instructions and do not panic,”“High school entrance announcements will be held as planned on March 16th,”— these two lines were broadcast repeatedly throughout local media.

From another angle, the recordings of the TEPCO video conference shows that Fukushima Prefecture requested TEPCO make a public announcement saying “the explosion in the Unit 3 at Fukushima Daiichi will not cause health damage.” Appalled by the request, thinking they “couldn’t say such an irresponsible thing,” TEPCO decided to “ask the central government to suppress Fukushima Prefecture,”—as evidently recorded during the video conference.

However Fukushima Prefecture repeatedly expressed that in the “Nakadōri” region—which includes the prefectural capitol, Fukushima City, and the commercially and industrially flourishing Koriyama City—there would be zero risk of health damage from radiation.

There has been a use of protective measures like wearing long-sleeves and masks for school children, which may have been a globally familiar sight through media reports. However this was not a recommendation or an order issued by Fukushima Prefecture, but rather a result of demands from local PTAs to boards of education in individual school districts.

Towards the end of March 2011, right before the school year resumed, the Fukushima governor was seen out in local grocery stores saying “Fukushima today is business as usual,” in which he began a campaign to “dispel harmful rumors” about local agricultural produce being contaminated by radiation. The governor also opposed widening the evacuation zone beyond the 20km radius of the nuclear power plant, and has repeatedly made remarks to avoid increasing the number of evacuees from outside the official evacuation zone.

As a result, aside from two local Fukushima newspapers, NHK, and four private television networks in addition to NHK Radio and Radio Fukushima, there was little to no mention of messages from outside Fukushima offering free housings and support networks for voluntary evacuees. Fukushima Prefecture also prohibited the use of not only public conference centers, but private facilities for hosting “counseling room” for evacuation as well. People around me practically had no knowledge of local autonomous support groups offering evacuation support. I have heard numerous times that “there is no evacuation order from outside the prefecture, meaning we have been abandoned.” In fact, it was Fukushima Prefecture who had been interfering with such efforts to reach our community.

3. Hiroshi Kainuma, “the Sociologist”

In 2011, an author from Fukushima became renowned after publishing the book “Fukushima’ theory–the birth of a nuclear village,” based on a thesis he wrote as a sociology student at the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Sciences. His name is Hiroshi Kaiuma, born in Iwaki City, Fukushima, and graduated from the University of Tokyo Literature department at the age of 25 and advanced to the graduate program. I must note that this is difficult to grasp if you are not well-connected within Fukushima. But in short, Iwaki City, where Mr. Kainuma was born and raised, has very little connection to the Futaba district which hosts TEPCO’s power plant. In terms of large-scale trading areas, while the Futaba district is part of the Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture trade area, Iwaki City would be part of Mito City in Ibaraki Prefecture. In any case, Mr. Kainuma did not have strong connections to the Fukushima Prefectural government prior to March 11th, 2011.

Since the meltdown, however, he has somehow become “the Fukushima spokesperson who speaks about Fukushima on TV and radio.”

Additionally, I have written several critiques of his writings, one of which can be found on the following link (in Japanese): “Personal note on “‘Fukushima’ theory–the birth of a nuclear village”

4. Hiroshi Kainuma and the Fukushima Prefectural Government

After 3.11, his master’s thesis was published in books and he began to be featured in various media, including an appearance as a commentator on the popular evening program “Hodo Station (News Station).” We must note that the content of his remarks have been consistent—such as, “The acceptance of nuclear power plant by local communities was necessary for the regions’ survival”; “Those outside of Fukushima protesting against nuclear energy do not understand the reality of nuclear-hosting communities.” His views and comments on the anti-nuclear movement have been antagonistic from the beginning, for example, “People who oppose nuclear energy are rubbing local communities the wrong way.”

Mr. Kainuma currently holds the title of Junior Researcher of the Fukushima Future Center for Regional Revitalization, but at the same time he is a PhD student at the University of Tokyo. While it would be appropriate to call him a sociology researcher, I feel it’s an overestimation to refer to him as a sociologist.

Currently the gist of Mr. Kainuma’s speech is towards the “recovery of Fukushima in visible forms” and its target audience is outside Fukushima Prefecture. While many others have in fact been referring to “bags” jammed with contaminated waste—seen everywhere and impossible to be ignored upon entering Fukushima—Mr. Kainuma continues to emphasize the “ordinary Fukushima” without mentioning the bags.

I see the previous governor of Fukushima, Yuhei Sato, in Mr. Kainuma in many ways, like in his seeming lack of experience interacting with people in temporary housings immediately following the meltdowns, or with shelter residents still living with much confusion and inconveniences as a result of the disaster.

Even the current Fukushima governor does not seem to have made too many visits to temporary shelters during or after elections.

To those who evacuated Fukushima to outer prefectures like myself, the Prefecture kept even more distance. By principle, they never made any official inspection visits to meet the evacuees. There is a notable lack of inspection visits not only in remote areas such as Hokkaido, but also in places like Yamagata and Niigata which are adjacent to Fukushima Prefecture.

In the wake of the disaster, though there was housing support for those who evacuated the areas outside of Fukushima as well, such efforts have gradually died down—as of March 2016, state subsidies for housing would be available only for evacuees who are from Fukushima. In addition, the housing subsidy program for those who evacuated the non-restricted zone will end in March 2017. However, there is no housing program for returning residents to Fukushima even if they decide to move back there.

Starting March 2017, voluntary evacuees still living in outer prefectures need to choose one of the three following choices:

1) Return home to Fukushima while paying out-of-pocket for most of the expenses associated with the move and your life thereafter. 2) Continue living outside Fukushima while relinquishing your rights to access resources as a disaster victim 3) Upon proving your need for financial assistance, receive housing subsidies for up to 2 years to live in privately-owned housing.

The reason for this policy change was credited to correspondence between the Minister of Environment and the Nuclear Regulatory Authority, a non-governmental agency to provide scientific grounds for nuclear policy. The Minister of Envirnoment asked the NRA if “it is considered desirable to evacuate the areas that don’t have restrictions” to which the NRA answered, ”these areas are no longer fit to be evacuated.” It should be noted that there was no legal ground for this correspondence to be treated as official; how this exchange was reviewed and by whom is unknown.

Based on this document issued by the NRA, the Japanese government made a Cabinet decision to largely reduce support for evacuees through the Nuclear Accident Child Victim’s Support Law.

Following this decision, Fukushima Prefecture also determined its policy would end support for the voluntary evacuees from non-restricted areas.

Hiroshi Kainuma is working from an assumed role to justify such policy of Fukushima Prefecture, utilizing his position as a so-called sociologist. Even if he has ideas and views that differ from Fukushima Prefecture’s policy, he does not speak about them on media or at talk events.

For instance, when Mr. Kainuma was relatively unknown before 3.11, he had reportedly interviewed local anti-nuclear activists. Another instance tells us that although he had met and interviewed several people who have moved voluntarily out of the non-restricted areas, he proceeds to ignore the voices and opinions of them as though they had never existed.

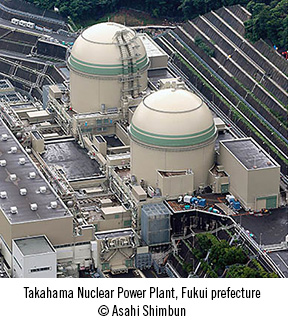

Last year, nuclear reactors in Japan started resuming operation. Mr. Kainuma has not been seen or heard expressing opposition to it. Neither Fukushima Prefecture nor the Prefectural Assembly expresses any intentions to oppose nuclear restorations.

5. The current presence of “Hiroshi Kainuma”

Through the circumstances described above, Hiroshi Kainuma is working so as to be portrayed by the media as a Fukushima Prefecture spokesperson, intent on selling “business-as-usual” appeal and depicting a Fukushima that “overcame a nuclear disaster.”

Meanwhile, and quite unfortunately, many Fukushima residents agree with his words and actions. Just as there are many people hoping to forget the scars from the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake, there are many who explicitly “do not evacuate,” comprising an overwhelming majority of the Fukushima population and wishing to forget and move past the disaster and nuclear crisis.

Here we have an academic scholar who speaks for us and to those who are outside Fukushima as well, saying to leave the nuclear disaster in the past.

Thus, this concludes the significance of Hiroshi Kainuma’s existence today.

東京電力福島原子力発電所事故発生前後から現在までの、福島県庁と開沼博氏達による被災者への対応

宍戸 俊則

自己紹介

自己紹介

筆者は、2011年7月31日まで約25年半の間、福島県の県立高等学校正規雇用教員として働きました。最初の4年間は、福島第一原発がある双葉町にある県立双葉高校の教員でした。そこで、原発作業員の過酷な労働条件(例:1日の被曝限度を10分で超えるので、拘束時間は8時間なのに実労働時間は10分で、主に原発配管から漏れる水を雑巾で拭いて集めるのが作業)などの例も聞きました。原発作業員がガンなどで死亡した場合、労災は認められない代わりに、一時金としては異例なほど高額な現金を遺族に支給する例も多数見聞しました。

原発事故発生時は、事故原発から直線距離で53kmの自宅に妻と子ども二人で住み、同じく直線距離で60kmの県立高校の教員でした。事故発生後、筆者の勤務地である福島市では2011年3月15日夕方に、空間線量で最大23μSv/hを超える汚染が公式に測定・公表されましたが、翌16日には例年と同じように、屋外で県立高校の合格発表を正午から、屋内で実行しました。発表前の職員会議では、筆者を含む数人が発表方法の再考等を校長に訴えたが、「福島県庁から強い支持が出ていて、校長にも選択権はない」という理由で、合格発表は屋外で強行されました。

4月以降、筆者が勤務する県立高校では、体育の屋外授業を行わない以外は、福島県教育委員会も学校も被曝防護対策を行いませんでした。屋外での運動部の練習・試合は通常通り行われました。屋内の運動競技の選手も学校外の道路を走る練習を、被曝防護措置なしで行われました。屋外から屋内に入った時のうがい、手洗い、着替え、シャワー等の体表除染も不要とされていました。多少知識が有る筆者は、可能な限りの体表汚染の除去などを生徒にアドバイスしていました。しかし、授業中に屋外から教室内に放射性物質が入ることを防ごうと生徒に指導したことを理由に福島県教育委員会から公式の「指導」を受け、以後放射性物質や原発について生徒に話すことを、県教育委員会から禁止されました。生徒を被曝防護することを公式に禁じられた筆者は、家族とともに北海道札幌市に家族避難しました。避難してみると、私たち自主避難者に対しても、指示地域から避難した人たちと同じように、家賃補助を福島県が支払う制度がありました。(2012年12月28日までに申し込んだ人まで有効で、今後新しく避難する人には支払われません。)

北海道でパートタイムの教員をしていますが、公立高校には福島県教育委員会から、人事異動に関する干渉があることがわかったので、その後は私立高校のパートタイムの教員を行いながら、原発被害訴訟の原告や、避難者団体のメンバーとして生活しています。

1. 福島県庁と東京電力福島原発事故 東京電力福島第1原発、特に1号機と2号機は、米国メーカーが全ての建設を終えて、引き渡した物でした。3号機から6号機は、その後、日本独自の「改良」を加えたものでした。 細かい点を説明する余裕がないので、最小限の記述にとどめますが、東京電力福島第一原発は、運転開始直後から頻繁に事故を繰り返し、作業員の平均被曝線量も他の原発の2倍から10倍程度と高く、その上に多くの重大な事故を福島県や日本政府に隠していたプラントでした。その3号機で、日本で余って困っているプルトニウムを減らすためのプルサーマル発電をおこなおうと計画した際には、当時の佐藤栄作久福島県知事がどうしても同意しませんでした。日本政府は、「収賄額ゼロ円の収賄罪」でそれまでの知事を逮捕し、辞職に追い込んで、佐藤雄平氏を新知事にしました。以上のように、福島県知事という役職、福島県庁という組織は、東京電力よりも弱い権力しか持っていませんでした。

2. 原発事故と福島県庁

2011年3月11日、福島県を含む広域を巨大地震が襲った時に、災害対策本部として使う予定だった福島県庁は、地震の揺れで損壊し、隣の小さな建物に臨時の対策本部機能を移しました。その後の20回以上の災害対策本部会議は、議事録も資料も何も公開されていません。25回目ごろからようやく、議事録が残るようになりました。

臨時の県災害対策本部には、衛星携帯電話が2回線あるだけだと言われています。その後少しずつ通信インフラが整備されていったとされていますが、この時期の公的な検証は行われていないので原発立地自治体との連絡、日本政府との連絡、東京電力との連絡、避難指示の伝達、などがどうなっていたのかは、まだ不明のままです。3月14日夕方に福島県知事が「あわてないで指示に従う事。16日に県立高校の合格発表を行う事」を指示したことだけが公表され、福島県内のあらゆるメディアを使って繰り返し報道されました。

他方、東京電力テレビ会議のビデオによると、「『第一原発3号機の爆発では、健康被害は出ない』と東京電力から発表してほしい」という要望が福島県庁から東京電力に行われたことが記録されています。「そんな無責任な事を言えるはずがないので、政府の方から福島県庁を抑えてくれるように依頼しよう」という話でまとまったように、ビデオには記録されています。

福島県庁は、県庁所在地がある福島市、商業と工業が盛んな郡山市などを含む「中通り」には健康影響の可能性さえもない、と繰り返し表明しました。 映像としてみた人が多い、小学生や中学生のマスク着用・長袖長ズボンの登下校も、福島県庁が推奨や通達を出したのではなく、PTAの保護者からの要望で、市町村教育委員会が推奨や通達を出した結果です。学校再開前の2011年3月末には、福島県知事は福島市内の大規模小売店の店頭に出て、「福島は『ふつうの福島』だ」と言いながら、福島県差農産品の「風評被害払拭」キャンペーンを始めています。また福島県知事は、避難指示区域を事故原発から半径20km以遠に広げることに反対し、避難指示区域外からの避難者が増える動きが出ないように繰り返し発言しています。

そのため、福島県内の2種類の地元新聞、NHKと4つの民間放送テレビ、NHKラジオとラジオ福島のようなメディアでは、「無償で避難を受け入れる」というような申し出を福島県内に流す事は、ごく少数の例外を除いてありませんでした。また、公共の組織だけでなく民間の会議場などを「県外避難相談所」として提供することさえも禁止しました。筆者の周囲では「県外から避難受け入れの呼び掛けがないという事は、私たちは見捨てられたという事なのか」というような言葉を何度も聞きましたが、実際には、福島県庁が妨害していたのです。

そのため、福島県内の2種類の地元新聞、NHKと4つの民間放送テレビ、NHKラジオとラジオ福島のようなメディアでは、「無償で避難を受け入れる」というような申し出を福島県内に流す事は、ごく少数の例外を除いてありませんでした。また、公共の組織だけでなく民間の会議場などを「県外避難相談所」として提供することさえも禁止しました。筆者の周囲では「県外から避難受け入れの呼び掛けがないという事は、私たちは見捨てられたという事なのか」というような言葉を何度も聞きましたが、実際には、福島県庁が妨害していたのです。

3. 開沼博という「社会学者」

2011年、東京大学大学院学際情報学府修士論文として書いていた文章を元にした『「フクシマ」論 原子力ムラはなぜ生まれたのか』という書物が話題になった人物がいます。福島県いわき市で生まれ、25歳で東京大学文学部を卒業し、大学院に進んだ開沼博氏です。福島県と濃密な関係を持つ人間でないと理解しがたいことですが、開沼氏が生まれ育ったいわき市は、東京電力の原発がある双葉地区とは関係が薄い地域です。大規模商圏として考えるならば、双葉地区は宮城県仙台市の商圏に入り、いわき市は茨城県水戸市の商圏に入ります。いずれにしても311以前、開沼氏は福島県庁との接点はそれほど強くありません。それがどうしたわけか、原発事故発生後、「福島の代表としてラジオやテレビ、イベントで話をする人」という存在になってしまいました。

3. 開沼博という「社会学者」

2011年、東京大学大学院学際情報学府修士論文として書いていた文章を元にした『「フクシマ」論 原子力ムラはなぜ生まれたのか』という書物が話題になった人物がいます。福島県いわき市で生まれ、25歳で東京大学文学部を卒業し、大学院に進んだ開沼博氏です。福島県と濃密な関係を持つ人間でないと理解しがたいことですが、開沼氏が生まれ育ったいわき市は、東京電力の原発がある双葉地区とは関係が薄い地域です。大規模商圏として考えるならば、双葉地区は宮城県仙台市の商圏に入り、いわき市は茨城県水戸市の商圏に入ります。いずれにしても311以前、開沼氏は福島県庁との接点はそれほど強くありません。それがどうしたわけか、原発事故発生後、「福島の代表としてラジオやテレビ、イベントで話をする人」という存在になってしまいました。

なお、開沼氏の修士論文を書籍化したものに対する筆者自身の批評は複数あるのだが、とりあえず《『「フクシマ」論 原子力ムラはなぜ生まれたのか』に対する個人的メモ》でまとめてあります。

4. 開沼博と福島県庁 311の後、修士論文が書籍化され、様々なメディアに取り上げられ、「報道ステーション」のコメンテーターとしても一度起用されています。が、発言の内容は「原発立地自治体が原発を受け入れたのは、その地域を存続させるための必然的な選択だった」とか「県外で言葉を発している人には、原発立地自治体のことはよくわかっていない」「原発反対派の人々は、地元の人々の気持ちを逆なでしている」など、反原発・脱原発の人々への反感が最初から際だっていました。

現在、開沼博氏の肩書は「福島大学うつくしまふくしま未来支援センター特任研究員」という呼称が先頭に書かれていることが多いのですが、同時に東京大学大学院博士課程在籍の博士課程学生でもあります。社会学「研究者」と呼ぶのは適切でしょうが、「社会学者」と呼ぶのは、過大評価だと筆者は感じています。 開沼氏の現在の言論の力点は、「眼に見える形での福島の復興」を福島県外に向けて、しかも福島県の外で発信する事に置かれています。他の多くの論者が、福島県内に立ち入るだけでどうしても目に付いてしまう「除染廃棄物」が詰まった「フレコンバッグ」に言及する中で、それには触れずに「ふつうの福島」を強調します。 前の知事の佐藤雄平氏と行動のイメージが重なる部分が他にもいくつかあるのですが、原発事故発生直後の混乱した避難所や、さまざまな不自由を抱えながら生活を続ける仮設住宅の避難者を訪問する姿が浮かびません。

現在の福島県知事も、知事選挙中や、就任直後は仮設住宅を訪問することはほとんどないようです。筆者たちのような、県外への避難者に対しては、避難元が指示区域外か指示区域内かを問わず、福島県庁職員が直接状況を視察に来たりすることは、原則的にありませんでした。北海道のような遠隔地ばかりではなく、福島県に隣接している山形県や新潟県への避難者の状況視察も行われていません。2011年事故発生直後は、受け入れ自治体側の判断などで福島県外からの原発事故による避難者に対しても住宅費用を支援してくれる例があったのですが、徐々にその避難元地域が限定されていき、2016年3月には原発事故による区域外避難に対する住宅支援を認めるのは、福島県内からの避難者限定になります。そして、福島県内からの区域外避難者に対しての住宅支援は、2017年3月で打ち切りになります。では、区域外避難者の帰還を受け入れる福島県内の住居があるかというと、ほとんど準備されていません。

2017年3月以後、区域外避難者は原則的に、次の3つから選ぶことになります。 ほぼ全額身銭を切って福島県内に帰るか。原発事故の被害者であると行政に認められない状態で福島県外で生活するか。著しく所得が低いことを証明して民間賃貸住宅への居住にたいする金銭的支援を2年間限定で受けるか。 このような状況になった理由は、環境副大臣が原子力規制委員会(行政から独立している科学的判断をするための組織)に対して「現在避難指定されていない区域は避難することが望ましいような状況か」と質問したことに対して、原子力規制庁(行政組織の一部)が「新たに避難する状況にはない」という返答を行ったことによります。なおこの文書のやり取りは、公的な組織同士がやり取りする文書の形式が整っておらず、誰がどのように検討した結果なのか分りません。

原子力規制庁から出たこの文書を根拠にして、日本政府は「原発事故子ども・被災者支援法」による支援を大幅に縮小する閣議決定をしました。 政府の閣議決定を受けて、福島県庁も区域外避難者への支援を打ち切る方針を出しました。 開沼博氏は、そのような福島県庁の方針を「社会学者」という肩書で正当化する役割を担って、活動しています。福島県の方針とは違う意見の人から話を聞いても、それをメディアや集会で紹介することはありません。例えば、311以前、開沼氏が無名だった時代にはその当時地元で活動していた反原発派にもインタビューしています。あるいは、311の後区域外避難している人にも少数ながらインタビューしています。しかし、そういう人達の声や意見は、まるで聞いたことさえないかのように無視します。昨年から、日本国内で原発の再稼動が始まりました。が、それに対して開沼氏が反対の意見を表明することはありません。福島県庁も県議会も「再稼動反対」の決議や意思表示をすることはありません。

5. 現在の「開沼博」という存在 以上のような経緯を経て、開沼博氏は、福島県庁の代弁者として、メディアに露出して「ふつうの福島」を宣伝して、「原発事故を乗り越えた福島」の強調を行うスポークスマンと化しているのです。そして、非常に残念なことながら、福島県内在住者の多くは、開沼氏の言動に賛同しています。阪神淡路大震災の後、可能な限り震災の傷跡を忘れたがった人が多いように、福島県の人口の圧倒的多数を占める「避難していない人」は震災も原発事故も過去のことにして、忘れたいのです。 原発事故を過去のことにして、福島県外の人にも過去のこととして忘れてもらうための学問の側からの発言者。 それが、現在の開沼博氏の存在意義になっていると筆者は結論します。